A Brief History of Western Civilization

THE UNEINISHEDLEGACY

高级英语选修课系列教材·历史与文化系列

西方文明史

(第五版) (精编普及版)

马克·凯什岚斯基 (Mark Kishlansky)[美]帕特里克·吉尔里(Patrick Geary) 著帕特里夏·奥布赖恩(Patricia O’Brien)

王建平 改编

Authorized Reprint from the English language edition, entitled A Brief History of Western Civilization: The Unfinished Legacy, 5e, 9780321431042 by Mark Kishlansky, Patrick Geary, Patricia O'Brien, published by Pearson Education, Inc., Copyright \copyright 2007 by Pearson Education, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage retrieval system, without permission from Pearson Education, Inc.

ENGLISH language edition published by CHINA RENMIN UNIVERSITY PRESS CO., LTD., Copyright \copyright 2021.

ENGLISH language adaptation edition is manufactured in the People's Republic of China, and is authorized for sale only in People's Republic of China excluding Hong Kong and Macau.

本书英文改编版由培生教育出版公司授权中国人民大学出版社合作出版,未经出版者书面许可,不得以任何形式复制或抄袭本书的任何部分。本书封面贴有PearsonEducation(培生教育出版集团)激光防伪标签。无标签者不得销售。仅限于中华人民共和国境内(不包括中国香港、澳门特别行政区和中国台湾地区)销售发行。

北京市版权局著作权合同登记号图字:01-2008-4078

图书在版编目(CIP)数据

西方文明史:第五版:精编普及版:英文/(美)凯什岚斯基,(美)吉尔里,(美)奥布赖恩著;王建平改编

一北京:中国人民大学出版社,2015.12

书名原文:A Brief History of Western Civilization:The Unfinished Legacy(5th Edition)

高级英语选修课系列教材.历史与文化系列

ISBN978-7-300-15156-4

I. ① 西.…ⅡI. ① 凯…. ⊚ 吉. ③ 奥. ④ 王.ⅢI. ① 文化史-西方国家-通俗读物-英文IV. ① K103-49

精编普及版使用说明

马克·凯什岚斯基、帕特里克·吉尔里、帕特里夏·奥布赖恩所著的《西方文明史(第五版)》(ISBN:9787300096796)试图从世界文明彼此联系互动的视角,全方位地展示西方文明繁复曲折的发展历程。作为新史学研究的产物,这部著作并没有过度褒扬西方民族性、制度、文化更替演进的宏大历史叙事,或仅仅呈现民族国家兴亡和英雄人物沉浮的刻板历史。《西方文明史》把西方文明的发展历程作为一条主线来讲述,以使读者真正有机会了解西方文明史的核心观点,但作者并未局限于欧洲历史的范围,而是将西方文明置于一个更广阔的领域,一个与世界其他地区、文明和民族互动的历史语境下,因为这些西方以外的地区、文明和民族与西方世界存在着相互间的影响。作者突破了欧洲中心史观,采用一种客观的、联系的和发展的观点来追溯西方文明的历史,循着历史时间的流动,勾勒西方文明与世界其他文明交互影响、相互渗透的演进历史,透过丰富生动的历史细节,探索决定西方文明发展形态的真正根基和多元文化基因。

在《西方文明史(第五版)(精编普及版)》中,我们力求保留原作中上述西方文明史的叙事主线,同时兼顾原作中西方文明与世界其他地域文明之间交流的线索,努力使其在连续性和变化方面能达到完美的融合。改编之后的版本仍然保留有前几版中的主要框架结构、章节设计以及一些非常成功的特点。书中每章首尾之处的导言和结论都简要地概括出主要历史时期的要旨。前几版中有着大量的地图和插图,由于篇幅所限,改编之后的版本只保留了原作中最为经典的插图,用以突出和补充文字内容。本版将原作的30章压缩为15章,对部分压缩的章节进行结构调整,做了重新编排。主要调整的部分如下:将原书的希腊文明(ClassicalGreek)的两章(第二章和第三章)合并为一章;将古罗马文化(Classical Roman)的三章的篇幅(第四章、第五章、第六章)整理成一章;将“中世纪”(Middle Ages)的三章(第八章、第九章、第十章)压缩为一章;将“现代欧洲”(ModernEurope)原有的三章(第十五章、第十六章、第十七章)整合为一章;将“十八世纪欧洲”(18th CenturyEurope)的第十八章和第十九章压缩为一章;将十九世纪(19thCentury)的三章(第二十一章、第二十二章、第二十三章)整合为一章;将“二十世纪:欧洲与世界”(20th Century:Europe and the World)的第二十四章和第二十五章压缩为一章。由于删节带来的承上启下文字过渡,对部分内容进行修改和编辑,同时,保留了原作中的二、三级标题。改编之后的版本保留了原书每章最后的“思考题”(QUESTIONS FORREVIEW)、“西方文明网上资源”(DISCOVERINGWESTERNCIVILIZATIONONLINE)和“扩展阅读书目”(SUGGESTIONSFORFURTHER READING)和全书最后的“词汇表”(Glossary)。为了方便教学使用,本书在每章后面增加了“关键词”(KeyTerms)的中文释义。同时提供了电子版教学课件和扩展阅读的视频材料,请登录中国人民大学出版社官方网站:http://www.crup.com.cn查找本书后下载使用,如有疑问,也可以联系我们索取。

出版社联系方式:

电话:010-62512737,010-62513265,010-62515580,010-62515573,010-62515576

E-mail:huangt@crup.com.cn, wangxw@crup.com.cn, chengzsh@crup.com.cn, crup_wy@163.com, jufa@crup.com.cr

作为介绍西方文明发展史的一本畅销教材,本书不仅全面系统地讲述了西方文明的发展历史,同时各种新颖的阅读版块,如每章开篇的“引言”和围绕该章的主题插图以及穿插其中的“文史栏目”,既能锻炼学生对于历史文化的视觉敏感度,又活跃历史性的思维,激发对于文明进程的宏观考察和对具体历史文化现象的深人思考。另外,此书还配有专门学习网站和拓展阅读书目,附加课本知识引申和延展,从而满足学生的求知需求。无论在知识性还是可读性方面,《西方文明史》都将是一部有价值的西方文明史入门书。

PREFACEIX ABOUTTHEAUTHORSXIV

INTRODUCTION THEIDEAOFWESTERNCIVILIZATION 2

CHAPTER 1 THE FIRST CIVILIZATIONS 4

IINTRODUCTION4

BEFORECIVILIZATION5 The Dominance of Culture5 Social Organization, Agriculture, and Religion 6

MESOPOTAMIA 6 The Ramparts of Uruk 7 Tools: Technology and Writing 7 Gods and Mortals in Mesopotamia7 Hammurabi and the Old Babylonian Empire 8

THE GIFTOFTHENILE10 Tending the Cattle of God10 Democratization of the Afterlife11

BETWEENTWOWORLDS11 The Hebrew Alternative11 A King Like All the Nations 12 Exile13

NINEVEHANDBABYLON13 The Assyrian Empire14 The New Babylonian Empire 14

CONCLUSION 14 QUESTIONS FOR REVIEW15 VOCABULARY15 DISCOVERINGWESTERN CIVILIZATION ONLINE16 SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER READING17

GREECEINTHEBRONZEAGE TO700B.C.E.20 Islands of Peace 20 Mainland of War 21 The Dark Age 21

ARCHAIC GREECE,700-500 B.C.E.22 Ethnos and Polis 22 Technology of Writing 23 Gods and Mortals 23 Myth and Reason 23 Art and the Individual 24 Democratic Athens 25

CLASSICALANDHELLENISTICGREECE,500-100

B.C.E.25 ALEXANDER AT ISSUS 25

ATHENIAN CULTUREIN THEHELLENICAGE26 The Examined Life 26 Understanding the Past 27 Athenian Drama 28 Philosophy and the Polis 28 The Rise of Macedon 29 The Empire of Alexander the Great30 Binding Together an Empire 30

THEHELLENISTICWORLD31 Urban Life and Culture 31 Alexandria 32 Architecture and Art 32 Hellenistic Philosophy 32 Mathematics and Science 33

CONCLUSION 34 QUESTIONS FOR REVIEW34 VOCABULARY34 DISCOVERINGWESTERNCIVILIZATION ONLINE36 SUGGESTIONSFORFURTHERREADING37

CHAPTER 2GREEK PERIOD 18

CHAPTER 3

THE ROMAN PERIOD 38

THEWESTERNMEDITERRANEANTO509B.C.E.39 Carthage: The Merchants of Baal39 Italy's First Civilization 39

FROM CITY TO EMPIRE,509-146 B.C.E.41 Latin Rome 41 Etruscan Rome 41 Rome and Italy 41

REPUBLICANCIVILIZATION42 Farmers and Soldiers42 Roman Religion 42 Republican Letters 42

THECRISISOFROMANVIRTUE43

IMPERIALROME,146B.C.E.-192C.E.43 THEALTAROFAUGUSTANPEACE43

THEPRICEOFEMPIRE,146-121B.C.E.44 Winners and Losers44

THEEND OF THEREPUBLIC45

THEAUGUSTANAGEANDTHEPAXROMANA47

RELIGIONS FROM THEEAST49 The Origins of Christianity50

CONCLUSION52 QUESTIONSFORREVIEW52 VOCABULARY52 DISCOVERINGWESTERNCIVILIZATION ONLINE55 SUGGESTIONSFORFURTHERREADING55

CHAPTER 4 THETRANSFORMATIONOFTHE CLASSICAL WORLD,192-500 56

■INTRUDUCTION56 THE CRISIS OF THE THIRD CENTURY57 Enrich the Army and Scorn the Rest58 An Empire on the Defensive59 The Barbarian Menace59 THEEMPIRE RESTORED60 Diocletian, the God-Emperor60 Constantine, the Emperor of God 61 The Triumph of Christianity 62 IMPERIAL CHRISTIANITY 62 Divinity, Humanity, and Salvation 63 The Call ofthe Desert64

Monastic Communities65 TheBarbarization of theWest 66 The New Barbarian Kingdoms 67 The Hellenization ofthe East 68 CONCLUSION68 QUESTIONSFORREVIEW 69 VOCABULARY 69 DISCOVERINGWESTERNCIVILIZATION ONLINE70 SUGGESTIONSFOR FURTHER READING70

CHAPTER 5 THECLASSICALLEGACYIN THEEAST: BYZANTIUM ANDISLAM 72

■INTRODUCTION72 THE BYZANTINES73 Justinian and the Creation of the Byzantine State73 THERISE OFISLAM75 Arabia Before the Prophet 75 The Triumph of Islam75 The Spread of Islam 76 Authority and Government in Islam 76 Islamic Civilization 77 THE BYZANTINE APOGEE AND DECLINE,1000- 145377 The Disintegration of the Empire78 The Conquests of Constantinople and Baghdad 78 CONCLUSION 79 QUESTIONSFORREVIEW79 VOCABULARY80 DISCOVERINGWESTERNCIVILIZATION ONLINE81 SUGGESTIONSFORFURTHERREADING81

CHAPTER 6 THE WESTIN THE MIDDLE AGES82

■INTRODUCTION82 THEMAKINGOFTHEBARBARIANKINGDOMS, 500-75083 Italy: From Ostrogoths to Lombards84 Visigothic Spain: Intolerance and Destruction 84

The Anglo-Saxons: From Pagan Conquerors to Christian Missionaries84 The Franks: An Enduring Legacy 86 Creating the European Aristocracy 86

THECAROLINGIANACHIEVEMENT87 The Carolingian Renaissance 8

AFTER THE CAROLINGIANS:FROM EMPIRE TO LORDSHIPS88 Disintegration of the Empire 89

THE HIGH MIDDLE AGES89 The Church: Saints and Monks 90 Scholasticism and Urban Intellectual Life91

THEINVENTIONOFTHESTATE93 The Universal States: Empire and Papacy 93 The Nation-States: France and England 95

THESPIRITOFTHELATERMIDDLEAGES98 The Crisis of the Papacy 98 Discerning the Spirit of God100 Heresy and Revolt 100 Religious Persecution in Spain 101 Vernacular Literature and the Individual101

CONCLUSION 103 QUESTIONS FOR REVIEW103 VOCABULARY103 DISCOVERINGWESTERNCIVILIZATION ONLINE104 SUGGESTIONSFOR FURTHER READING104

CHAPTER 7 THEITALIANRENAISSANCE 106

IINTRODUCTION106 RENAISSANCESOCIETY107 Cities and Countryside 108 Production and Consumption 108 RENAISSANCEART109 An Architect, a Sculptor, and a Painter 110 Renaissance Style 110 Michelangelo 111 RENAISSANCE IDEALS112 Humanists and the Liberal Arts 112 Renaissance Science 113 Machiavelli and Politics114

THEPOLITICSOFTHEITALIANCITY-STATES114 Venice: A Seaborne Empire115 Florence: Spinning Cloth into Gold116 The End of Italian Hegemony, 1450-1527 117

CONCLUSION118 QUESTIONSFORREVIEW118 VOCABULARY118 DISCOVERINGWESTERNCIVILIZATION ONLINE120 SUGGESTIONSFORFURTHER READING120

CHAPTER 8 THE REFORM OF RELIGION122

IINTRODUCTION122 THEINTELLECTUALREFORMATION123 The Print Revolution 123 Christian Humanism 124 The Humanist Movement 125 The Wit of Erasmus 125 THELUTHERANREFORMATION 126 The Spark of Reform 126 The Sale of Indulgences 126 Martin Luther Challenges the Church 127 Martin Luther's Faith 127 From Luther to Lutheranism 128 The Spread of Lutheranism130 THEPROTESTANTREFORMATION 131 Geneva and Calvin 131 The English Reformation 132 The Reformation of the Radicals 134 THECATHOLIC REFORMATION 135 The Spiritual Revival 135 Loyola's Pilgrimage 136 The Counter-Reformation 137 The Empire Reacts 138 CONCLUSION 139 QUESTIONS FOR REVIEW 139 VOCABULARY 139 DISCOVERING WESTERNCIVILIZATION ONLINE 140 SUGGESTIONSFORFURTHERREADING140

CHAPTER9 THE PERIOD OFMODERN EUROPE142

■INTRODUCTION142 ECONOMICLIFE143 Rural Life 143 Town Life 145 Economic Change 146 SOCIALLIFE147 Social Constructs 147 Social Structure 148 Social Change 149 THE ROYAL STATE IN THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY 151 THE RISE OF THE ROYALSTATE151 Divine Kings 152 THE CRISES OF THE ROYAL STATE 154 The English Civil War 154 The English Revolutions156 THEZENITHOF THEROYALSTATE157 The Nature of Absolute Monarchy158 SCIENCE ANDCOMMERCEINEARLYMODERN EUROPE159 The New Science159 Heavenly Revolutions 159 Science Enthroned 162 TheMarketplace of the World163 The Colonial Wars164 CONCLUSION 164 QUESTIONS FOR REVIEW 165 VOCABULARY 165 DISCOVERING WESTERN CIVILIZATION ONLINE 166 SUGGESTIONSFORFURTHER READING167

CHAPTER 1OTHEENLIGHTENMENT,FRENCHREVOLUTIONAND NAPOLEONIC ERA168

■INTRODUCTION168 THE ENLIGHTENMENT169 The Spirit of the Enlightenment 169

The Impact of the Enlightenment172

EIGHTEENTH-CENTURYSOCIETY 173 The Bourgeoisie 173

THEFRENCHREVOLUTIONANDTHEFALLOF THE MONARCHY175 Declaring Political Rights 175 The Trials of Constitutional Monarchy176

EXPERIMENTINGWITHDEMOCRACY,1792-

1799177 The Revolution of the People177 The End oftheRevolution177

THE REIGN OF NAPOLEON,1799-1815178 Bonaparte Seizes Power 178 Decline and Fall 179

CONCLUSION 180 QUESTIONSFORREVIEW 181 VOCABULARY181 DISCOVERINGWESTERNCIVILIZATION ONLINE182 SUGGESTIONS FORFURTHER READING182

CHAPTER 11 EUROPE IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY 184

■INTRODUCTION184 THE TRADITIONALECONOMY185 The Agricultural Revolution185 THEINDUSTRIALREVOLUTIONINBRITAIN186 Britain First187 Cotton Is King 188 The Wages of Progress 188 THEINDUSTRIALIZATION OFTHECONTINENT190 THEBIRTHOFTHEGERMANEMPIRE191 BUILDING NATIONS:THEPOLITICS OF UNIFICATION191 The Crimean War 191 The United States:Civil War and Reunification193 Nationalism and Force193 REFORMINGEUROPEANSOCIETY193 The Second Empirein France,1852-1870193 The Victorian Compromise194 CHANGINGVALUESANDTHEFORCEOFNEW IDEAS194

Realism in the Arts 194

Charles Darwin and the New Science 195

Karl Marx and the Science of Society196

CONCLUSION196

QUESTIONSFORREVIEW197

VOCABULARY 197

DISCOVERING WESTERNCIVILIZATION ONLINE197 SUGGESTIONSFORFURTHER READING198

CHAPTER 12 EUROPE AND THE WORLD, 1870-1914 200

■INTRODUCTION200 EUROPEANECONOMYANDTHEPOLITICSOF MASSSOCIETY201 Regulating Boom and Bust 201 Challenging Liberal England 202 OUTSIDERSINMASSPOLITICS203 TheJewish Question and Zionism204 THEWESTAND THEWIDERWORLD204 African Art and European Artists 204 Art and the New Age 205 THEPOLITICSOFMAPMAKING206 THE EUROPEANBALANCE OFPOWER,1870- 1914207 Upsetting the European Balance of Power 207 THENEWIMPERIALISM209 Motives for Empire 209 THESEARCHFOR TERRITORYANDMARKETS211 The Scramble for Africa: Diplomacy and Conflict 211 Imperialism in Asia 214 The Imperialism of the United States 216 RESULTS OF A EUROPEAN-DOMINATED WORLD216 A World Economy 216 Race and Culture 217 CONCLUSION 217 QUESTIONS FOR REVIEW218 VOCABULARY218 DISCOVERINGWESTERNCIVILIZATION ONLINE219 SUGGESTIONSFORFURTHERREADING219

CHAPTER 13WARANDREVOLUTION,1914-1920220

■INTRODUCTION220 THEWAREUROPEEXPECTED221 Separating Friends fromFoes 222 ANEWKINDOFWARFARE 222 Technology and the Trenches 223 The German Offensive 223 War on the EasternFront 224 WarontheWesternFront225 War on the Periphery 226 ADJUSTINGTOTHEUNEXPECTED:TOTALWAR226 THERUSSIANREVOLUTIONANDALLIED VICTORY 226 Revolution in Russia 227 SETTLINGTHEPEACE 229 Wilson's Fourteen Points 230 Treaties and Territories 230 CONCLUSION 232 QUESTIONSFORREVIEW 232 VOCABULARY232 DISCOVERING WESTERNCIVILIZATION ONLINE234 SUGGESTIONSFORFURTHERREADING234

CHAPTER 14 THESECONDWORLDWAR 236

■INTRODUCTION236 EURROPEAFTER1918237 CRISISANDCOLLAPSEINAWORLDECONOMY238 International Loans and TradeBarriers238 The Great Depression239 Stalin's Rise to Power240 THERISE OFFASCIST DICTATORSHIPINITALY240 Mussolini's Italy240 Mussolini'sPlans forEmpire241 HITLER AND THE THIRDREICH241 Hitler's Rise to Power 242 Propaganda, Racism, and Culture 243 DEMOCRACIESIN CRISIS244

AGGRESSIONAND CONQUEST244 Hitler's Foreign Policy and Appeasement 244 The Destruction of Europe's Jews 246

ALLIEDVICTORY247 The Soviet Union's Great Patriotic War247 The United States Enters the War 249 Winning the War in Europe 249 Winning the War in the Pacific 250

CONCLUSION 250 QUESTIONSFORREVIEW 251 VOCABULARY 251 DISCOVERINGWESTERNCIVILIZATION ONLINE253 SUGGESTIONSFORFURTHERREADING253

■INTRODUCTION254 THEORIGINSOFTHECOLDWAR 255 The World in Two Blocs256 Decolonization and the Cold War257 THEWELFARE STATE ANDSOCIAL TRANSFORMATION258 THEENDOFTHECOLDWARANDTHE EMERGENCEOFANEWEUROPE258 THEWESTINTHEGLOBALCOMMUNITY259 European Union and theAmerican Superpower259 Terrorism: The“New Kind ofWar”261 CONCLUSION 264 QUESTIONSFORREVIEW 265 VOCABULARY265 DISCOVERINGWESTERNCIVILIZATION ONLINE267 SUGGESTIONSFORFURTHERREADING 267

GLOSSARY268

Whenwesetout towriteCivilization intheWest,wetried towrite,firstof all,abook that students would want to read. Throughout many years of planning, writing, revising. rewriting, and numerous meetings together, this was our constant overriding concern. Would the text work across the variety of Western civilization courses,with the different levels and formats that makeup thisfundamental course?Wealso solicited thereactions of scores of reviewers to this single question: “Would students want to read these chapters?" Whenever we received a resounding “No!" we began again—not just rewriting, but rethinking how to present material that might be complex in argument or detail or that might simply seem too remote to engage the contemporary student. Though all three of us were putting in long hours in front of computers, we quickly learned that we were engaged in a teaching rather than a writing exercise.And though thework was demanding, it was not unrewarding. We enjoyed writing this book, and we wanted students to enjoy reading it.We have been gratified to learn that our book successfully accomplished our objectives. It stimulated student interest and motivated studentstowant tolearn about Europeanhistory.Civilization in theWestwas successful beyond ourexpectations.

The text was so well received, in fact, that we decided to publish this alternative, brief version:A Brief History of Western Civilization: The Unfinished Legacy.In an era of rapidly changing educational materials,alternative formats and models should be available.We believe that students and general readers alike will enjoy a conveniently sized book that offers them a coherent, well-told story. In this edition of the brief text, we have enlarged and added detail to many of the full-color maps so that they are easier to see and use. We have also added a new feature,“Map Discovery” that teaches students to think critically about maps, have included new essays to give students a feel for the cultural exchanges that have taken place between the West and the non-West entitled“The West and the Wider World" and have replaced several of the chapter-opening“Visual Record” narratives.

APPROACH

The approach used in A Brief History of Western Civilization: The Unfinished Legacy, Fifth Edition,upholds and confirms a number of decisions made early in the writing of Civilization in the West. First, this brief, alternative version is, like the full-length text, a mainstream text in which most of our energies have been focused on developing a solid, readable narrative of Western civilization that integrates coverage of women and minorities into the discussion. We highlight personalities while identifying trends. We spotlight social history, both in sections of chapters and in separate chapters, while maintaining a firm grip on political developments.

Neither A Brief History of Western Civilization: The Unfinished Legacy nor Civilization in the West is meant to be an encyclopedia of Western civilization. Information is not included in a chapter unless it fits within the themes of that chapter. In both the full-length and brief versions of this text, we are committed to integrating the history of ordinary men and women into our narrative. We believe that isolated sections placed at the end of chapters that deal with the experiences of women or minority groups in a particular era profoundly distort historical experience.We call this technique“caboosing”and whenever we found ourselves segregating women or families or the masses, we stepped back and asked how we might recast our treatment of historical events to account for a diversity of actors. How did ordinary men, women, and children affect the course of world historical events? How did world historical events affect the fabric of daily life for men, women, and children from all walks of life? We also tried to rethink critical historical problems of civilization as gendered phenomena.We take the same approach to the coverage of central andeasternEurope that wedid towomen and minorities.Evenbefore theepochal events of thelate1980s and early1990s thatreturned this region totheforefront ofinternational attention,we realized that many textbooks treated theSlavic world as marginal to the history of Western civilization. Therefore, we worked to integrate more of the history of eastern Europe into our text than is found in most others and to do so in a way that presented these regions, their cultures, and their institutions as integral rather than peripheral toWesterncivilization.

FEATURES

In A Brief History of Western Civilization: The Unfinished Legacy, we wanted to present features that would have the most immediate and positive impact on our readers and fulfll our goal of involving students in learning. Therefore, this edition features the following:

The Visual Record: Pictorial Chapter Openers Geographical Tours of Europe Primary Source Documents DiscoveringWestern Civilization Online

CHANGESINTHENEWEDITION

In the fth edition of A Brief History of Western Civilization: The Unfinished Legacy we have made several changes to the book's content and coverage.

New!TheWest and theWider World New! Visual Record Pictorial Essays New! Key Terms and Glossary

Acknowledgements

We want to thank the many conscientious historians who gave generously of their time and knowledge to review our manuscript. We would like to thank the reviewers of the first four editions as well as those of the current edition. Their valuable critiques and suggestions have contributed greatly to the final product. We are grateful to the following:

Daniel F. Callahan, University of Delaware; Michael Clinton, Gwynedd-Mercy College; Bob Cole, Utah State University; Gary P. Cox, Gordon College; Peter L. de Rosa, Bridgewater State College; Frank Lee Earley, Arapahoe Community College; Steven Fanning, University of Illinois at Chicago; Patrick Foley, Tarrant County Collge; Charlotte M. Gradie, Sacred Heart University; Richard Grossman, Northeastern Illinois University; David Halamy, Cypress College; Gary J. Johnson, University of Southern Maine; Cynthia Jones, University of

Missouri atKansas City;JohnKemp,Truckee Meadows Community College;JanilynKocher, Richland Community College; Lisa M. Lane, MiraCosta College; Oscar Lansen, University of North Carolina at Charlotte; Michael R. Lynn, Agnes Scott College; Mark S. Malaszczyk, St. John'sUniversity;John M.McCulloh,KansasStateUniversity;David B.Mock,Tallahassee Community College;Don Mohr,Emeritus,University of Alaska,Anchorage;Martha G. Newman,University of Texas at Austin;Lisa Pace-Hardy,Jefferson Davis Community College; Marlette Rebhorn, Austin Community College; Steven G. Reinhardt, University of Texas at Arlington; Kimberly Reiter, Stetson University; Robert Rockwell, Mt.San Jacinto College; Maryloy Ruud,University of West Florida; Jose M. Sanchez,St. Louis University; Erwin Sicher, Southwestern Adventist College; Ruth Suyama, Los Angeles Mission College; David Tengwall, Anne Arundel Cormmunity Collge; Janet M. C. Walmsley, George Mason University; John E. Weakland, Ball State University; and Rick Whisonant, York Technical College.

Our special thanks go to our colleagues at Marquette University for their longstanding support, valuable comments, and assistance on this edition's design: Lance Grahn, Lezlie Knox, Timothy G. McMahon, and Alan P. Singer.

We also acknowledge the assistance of the many reviewers of Civilization in the West whose comments have been invaluable in the development of A Brief History of Western Civilization: The UnfinishedLegacy:

Joseph Aieta,III, Lasell College;Ken Albala,University of the Pacific; Patricia Ali, Morris College; Gerald D. Anderson, North Dakota State University; Jean K. Berger, University of Wisconsin, Fox Valley; Susan Carrafiello, Wright State University; Andrew Donson, University of Massachusetts, Amherst; Frederick Dotolo, St. John Fisher College; Janusz Duzinkiewicz, Purdue University; Brian Elsesser, Saint Louis University; Bryan Ganaway, University of Illinois; David Graf, University of Miami; Benjamin Hett, Hunter College; Mark M. Hull, Saint Louis University; Barbara Klemm, Broward Community College; Lawrence Langer, University of Connecticut; Elise Moentmann, University of Portland; Alisa Plant, Tulane University; Salvador Rivera, State University of New York; Thomas Robisheaux, Duke University; Ilicia Sprey, Saint Joseph's College; George S. Vascik, Miami University, Hamilton; Vance Youmans, Spokane Falls Community College; Achilles Aavraamides, Iowa State University; Meredith L. Adams, Southwest Missouri State University; Arthur H. Auten, University of Hartford; Suzanne Balch-Lindsay, Eastern New Mexico University; Sharon Bannister, University of Findlay; John W. Barker, University of Wisconsin; Patrick Bass, Mount Union College; William H. Beik,Northern Illinois University; Patrice Berger, University of Nebraska; Lenard R. Berlanstein, University of Virginia; Raymond Birn, University of Oregon; Donna Bohanan, Auburn University; Werner Braatz, University of Wisconsin, Oshkosh; Thomas A. Brady, Jr., University of Oregon; Anthony M. Brescia, Nassau Community College; Elaine G. Breslaw, Morgan State University; Ronald S. Brockway, Regis University; April Brooks, South Dakota State University; Daniel Patrick Brown, Moorpark College; Ronald A. Brown, Charles County Community College; Blaine T. Browne, Broward Community College; Kathleen S. Carter, High Point University; Robert Carver, University of Missouri, Rolla; Edward J. Champlin, Princeton University; StephanieEvans Christelow,Western WashingtonUniversity;Sister Dorita Clifford, BVM, University of San Francisco; Gary B. Cohen, University of Oklahoma; Jan M. Copes, Cleveland State University; John J. Contreni, Purdue University; Tim Crain, University of Wisconsin, Stout; Norman Delaney, Del Mar College; Samuel E. Dicks,

Emporia State University; Frederick Dumin, Washington State University Laird Easton, California State University, Chico; Dianne E. Farrll Moorhead State University; Margot C. Finn, Emory University; Allan W. Fletcher, Boise State University; Luci Fortunato De Lisle, Bridgewater State College; Elizabeth L. Furdell, University of North Florida; Thomas W. Gallant, University of Florida; Frank Garosi, Caljfornia State University, Sacramento; Lorne E. Glaim, Pacific Union College; Joseph J. Godson, Hudson Valley Community College; Sue Helder Goliber, Mount St. Mary's College; Manuel G. Gonzales, Diablo Valley College; Louis Haas, Duquesne University; Eric Haines, Bellevue Community College; Paul Halliday, University of Virginia; Margaretta S. Handke, Mankato State University; David A. Harnett, University of San Francisco; Paul B. Harvey, Jr., Pennsylvania State University; Neil Heyman, San Diego State University; Daniel W. Hollis, Jacksonville State University; Kenneth G. Holum, University of Maryland; Patricia Howe, University of St. Thomas; David Hudson, California State University, Fresno; Charles Ingrao, Purdue University; George F Jewsbury, Oklahoma State University; Donald G. Jones, University of Central Arkansas; William R. Jones, University of New Hampshire; Richard W. Kaeuper, University of Rochester; David Kaiser, Carnegie-Mellon University; Jeff Kaufmann, Muscatine Community College; Carolyn Kay, Trent University; William R. Keylor, Boston University; Joseph Kicklighter, Auburn University; Charles L. Killinger, II, Valencia Community College; Alan M. Kirshner, Ohlone College; Charlene Kiser, Miligan College; Alexandra Korros, Xavier University; Cynthia Kosso, Northern Arizona University; Lara Kriegel, Florida International University; Lisa M. Lane, MiraCosta Collge; David C. Large, Montana State University; Catherine Lawrence, Messiah College; Bryan LeBeau, Creighton University; Robert B. Luehrs, Fort Hays State University; Donna J. Maier, University of Northern Iowa; Margaret Malamud, New Mexico State University Roberta T. Manning, Boston College; Lyle McAlister, University of Florida; Therese M. McBride, College of the Holy Cross; David K. McQuilkin, Bridgewater College; Victor V. Minasian, College of Marin; David B. Mock, Tallhasse Community College;: Robert Moeller, University of California, Irvine; R. Scott Moore, University of Dayton; Ann E. Moyer, University of Pennsylvania; Pierce C. Mullen, Montana State University; John A. Nichols, Slippery Rock University; Thomas F. X. Noble, University of Virginia; J. Ronald Oakley, Davidson County Community College; Bruce K. O'Brien, Mary Washington College; Dennis H. O'Brien, West Virginia University; Maura O'Connor, University of Cincinnati; Richard A. Oehling, Assumption College; James H. Overfield, University of Vermont; Catherine Patterson, University of Houston; Sue Patrick, University of Wisconsin, Barron County; Peter C. Piccillo, Rhode Island Collge; Peter O'M. Pierson, Santa Clara University; Theophilus Prousis, University of North Florida; Marlette Rebhorn, Austin Community College; Jack B. Ridley, University of Missouri, Rolla; Constance M. Rousseau, Providence College; Thomas J. Runyan, Cleveland State University John P. Ryan, Kansas City Community College; Geraldine Ryder, Ocean County College; Joanne Schneider, Rhode Island Collge; Steven Schroeder, Indiana Universityof Pennsylvania; Steven C.Seyer, Lehigh County Community College; Lixin Shao, University of Minnesota, Duluth; George H. Shriver, Georgia Southern University; Ellen J. Skinner, Pace University; Bonnie Smith, University of Rochester; Patrick Smith, Broward Community College James Smither, Grand Valley State University; Sherill Spar, East Central University; Charles R. Sullivan, University of Dallas;: Peter N. Stearns, Carnegie-Mellon University Saulius Suziedelis, Millesville University; Darryl B. Sycher, Columbus State Community Collge; Roger Tate, Somerset Community

College; Janet A. Thompson, Tallahassee Community College; Anne-Marie Thornton, Bilkent University; Donna L. Van Raaphorst, Cuyahoga Community College; James Vanstone, John Abbot College; Steven Vincent, North Carolina State University; Richard A.Voeltz, Cameron University;Faith Wallis,McGill University; Sydney Watts,University of Richmond;Eric Weissman, Golden West College; Christine White, Pennsylvania State University; William HarryZee,GloucesterCountyCollege.

Each author also received invaluable assistance and encouragement from many colleagues, friends, and family members over the years of research, reflection, writing, and revising thatwentinto themaking of thistext:

Mark Kishlansky thanks Ann Adams,Robert Bartlett, Ray Birn,David Buisseret, Ted Cook, Frank Conaway, Constantine Fasolt, James Hankins, Katherine Haskins, Richard Hellie, Matthew Kishlansky, Donna Marder, Mary Beth Rose,Victor Stater, Jeanne Thiel, and the staffs of the Joseph Regenstein Library, the Newberry Library, and the Widener andLamontLibrariesatHarvard.

Patrick Geary wishes to thank Mary, Catherine, and Anne Geary for their patience, support, and encouragement. He also thanks Anne Picard, Dale Schofield, Hans Hummer, and Richard Mowrer for their able assistance throughout the project.

Patricia O'Brien thanks Christopher Reed for his loving support; Tristan Reed for his intellectual engagement; and Erin and Devin Reed for “keeping me in touch with the contemporaryworld."

Mark Kishlansky Patrick Geary Patricia O'Brien

ABOUTTHE AUTHORS

MARK KISHLANSKY Mark Kishlansky is Frank B. Baird, Jr., Professor of English and European History and has served as the Associate Dean of the Faculty at Harvard University. He was educated at the State University of New York at Stony Brook, where he first studied history, and at Brown University, where he received his Ph.D. in 1977. For 16 years, he taught at the University of Chicago and was a member of the staff that taught Western Civilization. Currently, he lectures on the History of Western Civilization at Harvard. Professor Kishlansky is a specialist on seventeenth-century English political history and has written, among other works, A Monarchy Transformed, The Rise of the NewModel Army,andParliamentary Selection:Social andPolitical Choice in EarlyModern England. From 1984 to 1991, he was editor of the Journal of British Studies and is presently the general editor of History Compass, the first on-line history journal. He is also the general editor for Pearson Custom Publishing's source and interpretations databases, which provide custom book supplements for Western Civilization courses.

PATRICK GEARY Holding a Ph.D. in Medieval Studies from Yale University, Patrick Geary has broad experience in interdisciplinary approaches to European history and civilization. He has served as the director of the Medieval Institute at the University of Notre Dame as well as directorfor the Centerfor Medieval and Renaissance Studies at the University of California,Los Angeles,where he is currently Distinguished Professor of History. He has also held positions at the University of Florida and Princeton University and has taught at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales in Paris, the Central European University in Budapest, and the University of Vienna. His many publications include Readings in Medieval History;BeforeFrance and Germany:The Creation and Transformation of theMerovingianWorld;Phantoms of Remembrance:Memoryand Oblivion at theEnd of theFirst Millennium;TheMyth of Nations:TheMedieval Origins of Europe; and Women at the Beginning: Origin Myths from the Amazons to the Virgin Mary.

PATRICIA O'BRIENis a specialist in modern French cultural and social history and received her Ph.D. from Columbia University. She has held appointments at Yale University, the University of California, Irvine, the University of California, Riverside, the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales in Paris, and the University of California, Los Angeles. Between 1995 and 1999, Professor O'Brien worked to foster collaborative interdisciplinary research in the humanities as director of the University of California Humanities Research Institute. Since 2004, she has served as Executive Dean of the College of Letters and Science at UCLA. Professor O'Brien has published widely on the history of French crime and punishment, cultural theory, urban history, and gender issues. Representative publications include The Promise of Punishment:Prisons in Nineteenth-Century France; \*The Kleptomania Diagnosis: Bourgeois Women and Theft in Late Nineteenth-Century France”in Expanding thePast:A Reader in Social History; and“Michel Foucault's History of Culture" in The New Cultural History, edited by Lynn Hunt. Professor O'Brien's commitment to this textbook grew out of her own teaching experiences in large, introductory Western civilization courses.She has benefitedfrom the contributions of her students and fellow instructors in her approach to the study of Western civilization in the modern period.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF WESTERN CIVILIZATION

THEIDEAOF WESTERN CIVILIZATION

The West is an idea. It is not visible from space. An astronautviewing the blue-and-whiteterrestrial sphere can make out the forms of Africa, bounded by the Atlantic, the Indian Ocean, the Red Sea, and the Mediterranean. Australia,the Americas, and even Antarctica are distinct patches of blue-green in the darker waters that surround them. But nothing comparable separates Asia from Europe, East from West. Viewed from 100 miles up, the West itself is invisible. Although astronauts can see the great Eurasian landmass curving around the Northern Hemisphere, the UralMountains—the theoreticalboundarybetweenEast and West—appear faint from space. Certainly they are less impressive than the towering Himalayas, the Alps, or even the Caucasus. People, not geology, determined that the Urals should be the arbitrary boundary between Europe and Asia.

Even this determination took centuries. Originally, Europe was a name that referred only to central Greece. Gradually, Greeks extended it to include the whole Greek mainland and then the landmass to the north. Later, Roman explorers and soldiers carried Europe north and west to its modern boundaries. Asia too grew with time. Initially, Asia was only that small portion of what is today Turkey inland from the Aegean Sea. Gradually, as Greek explorers came to know of lands farther east, north, and south, they expanded their understanding of Asia to include everything east of the Don River to the north and of the Red Sea to the south.

Western civilization is as much an idea as the West itself. Under the right conditions, astronauts can see the Great Wall of China snaking its way from the edge of the Himalayas to the Yellow Sea. No comparable physical legacy of the West is so massive that its details can be discerned from space. Nor areWestern achievements rooted forever in one corner of the world. What we call Western civilization belongs to no particular place. Its location has changed since the origins of civilization, that is, the cultural and social traditions characteristic of the civitas, or city.“Western” cities appeared first outside the “West,” in the Tigris and Euphrates river basins in present-day Iraq and Iran, a region that we today call the Middle East. These areas have never lost their urban traditions, but in time, other cities in North Africa, Greece, and Italy adapted and expanded this heritage.

Until the sixteenth century C.E., the western end of the Eurasian landmass was the crucible in which disparate cultural and intellectual traditions of the Near East, the Mediterranean, and northern and western Europe were smelted into a new and powerful alloy. Then “the West” expanded by establishing colonies overseas and by giving rise to the “settler societies” of the Americas, Australia and New Zealand, andSouthAfrica.

Western technology for harnessing nature, Western forms of economic and political organization, Western styles of art and music are—for good or ill—-dominant influences in world civilization. Japan is a leading power in the Western traditions of capitalist commerce and technology. China, the most populous country in the world, adheres to Marxist socialist principles—a European political tradition. Millions of people in Africa, Asia, and the Americas follow the religions of Islam and Christianity, both of which developed from Judaism in the cradle of Western civilization.

Many of today's most pressing problems are also part of the legacy of the Western tradition. The remnants of European colonialism have left deep hostilities throughout the world. The integration of developing nations into the world economy keeps much of humanity in a seemingly hopeless cycle of poverty as the wealth of poor countries goes to pay interest on loans from Europe and America. Hatred of Western civilization is a central, ideological tenet that inspired terrorist attacks on symbols of American economic and military strength on September 11, 2001, and that fuels anti-Western terrorism around the world. The West itself faces a crisis. Impoverished citizens of former colonies flock to Europe and North America seeking a better life but often finding poverty, hostility, and racism instead. Finally, the advances of Western civilization endanger our very existence. Technology pollutes the world's air, water, and soil, and nuclear weapons threaten the destruction of all civilization. Yet these are the same advances that allow us to lengthen life expectancy, harness the forces of nature, and conquer disease. It is the same technology that allows us to view our world from outer space.

How did we get here? In this book we attempt to answer that question. The history of Western civilization is not simply the triumphal story of progress, the creation of a better world. Even in areas in which we can see development, such as technology, communications, and social complexity, change is not always for the better. However, it would be equally inaccurate to view Western civilization as a progressive decline from a mythical golden age of the human race. The roughly 300generations since the origins of civilization have bequeathed a rich and contradictory legacy to the present. Inherited political and social institutions, cultural forms, and religious and philosophical traditions form the framework within which the future must be created. The past does not determine the future, but it is the raw material from which the future will be made. To use this legacy properly, we must first understand it, not because the past is the key to the future, but because understanding yesterday frees us to create tomorrow.

CHAPTER 1 THE FIRST CIVILIZATIONS

INTRODUCTION

The idea that we can visit with an ancestor from three hundred generations past seems incredible. And yet a discovery in the Italian Alps a decade ago has brought us face to face with Otzi (so-named for the valley where he was found), an ordinary man who faced a cruel death more than five thousand years ago. Otzi's perfectly preserved body, clothing, tools, and weapons allow us to know how people lived and died in Western Europe before it wasEurope--beforeindeed itwas theWest.

Otzi was small by modern European standards: he stood at just 5 feet 4 inches. Around 40 years old, he was already suffering from arthritis, and his several tattoos were likely a kind of therapy. He probably lived in a village below the mountain whose inhabitants survived by hunting, simple agriculture, and goat herding.

One spring day around 3000 B.C.E., Otzi enjoyed what would be his last meal of meat, some vegetables, and flat bread made of einkorn wheat. He dressed warmly but simply in a leather breechcloth with a calfskin belt covered by a leather upper garment of goatskin sewn together with animal sinews. Below, he wore leather leggings and sturdy shoes made of bearskin soles and deerhide tops, lined with soft grasslike socks. On his head was a warm bearskin cap.

Otzi carried an ax with a blade of almost pure copper and a flint knife in a fiber scabbard. He secured his leather backpack on a pack-frame made of a long hazel rod bent into a U-shape and reinforced with two narrow wooden slats.Among other things it held birch bark containers, one filled with materials to start a fire, which he could ignite with a flint he carried in his pouch. He also equipped himself with a multipurpose mat made from long stalks of Alpine grass and a simple first-aid kit consisting of inner bark from the birch tree—a substance with antibiotic and styptic properties. For so small a man, Otzi carried an imposing weapon: a yew-wood bow almost six feet long and a quiver of arrows. He must have been working on the weapon shortly before he died; the bow and most of the arrows wereunfinished.

For ten years after the discovery of Otzi's body, scholars and scientists studied his remains and speculated on why and how he died. Was he caught by a sudden storm or did he perhaps injure himself and die of exposure? And what was he doing so high in the mountains—six hours from the valley where he had his last meal, without adequate food or water? Finally, another X-ray of his frozen corpse revealed a clue: the shadow of a stone point lodged in his back.

Apparently, Otzi left the lower villages that fateful spring day frightened and in a great hurry. Alone at an altitude of over 10,000 feet, desperately trying to finish his bow and arrows, he was fleeing for his life, but his luck ran out. Otzi was shot in the back with an arrow. It pierced his shoulder between his shoulder blade and ribs, paralyzing his arm and causing extensive bleeding. Exhausted, he lay down in a shallow cleft in the snowy rocks. In a matter of hours he was dead, and the snows of centuries quietlyburiedhim.

This first chapter begins before Otzi with the origins of humankind and chronicles the great discoveries that led to the first urban-based civilizations of Mesopotamia and Egypt. It examines as well the semi-nomadic herding societies that lived on their margins and developed the first great monotheistic religious tradition.

the best-known finds, nicknamed “Lucy" by the scientist who discovered her skeleton in 1974, stood only about four feet tall and lived on the edge of a lake in what is now Ethiopia. Lucy and her band did not have brains that were as well developed as those of modern humans. They did, however, use simple tools such as sticks, bone clubs, and chipped rocks. Although small and relatively weak compared with other animals, Lucy's species of creatures--neither fully ape nor human—survived for over four million years.

BEFORECIVILIZATION

The human race was already ancient by the time that Otzi died, and civilization first appeared around 3,500 years before the Common Era, the period following the traditional date of the birth of Jesus. (Such dates are abbreviated B.C. for "before Christ” or B.C.E. for “before the Common Era"; A.D., the abbreviation of the Latin for “in the year of the Lord” is used to refer to dates after the birth of Jesus. Today, scholars use simply C.E. to mean the Common Era. To indicate an approximate date for an event that cannot be dated precisely, the abbreviation ca., or circa, “approximately” is used.) The first human-like creatures whose remains have been discovered date from as long as five million years ago. One of

Varieties of the modern species of humans, Homo sapiens ("thinking human"), appeared well over 100,000 yearsagoandspreadacross theEurasianlandmass and Africa. Early Homo sapiens lived in small kin groups of 20 or 30, following game and seeking shelter in tents, lean-tos, and caves. People of the Paleolithic era or Old Stone Age (ca.600,000-10,000 B.C.E.) worked together for hunting and defense and apparently formed emotional bonds that were based on more than sex or economic necessity. The skeleton of a man found a few years ago in Iraq, for example, suggests that although he was born with only one arm and was crippled further by arthritis, the rest of his community supported him and he lived to adulthood. Clearly, his value to his society lay in something more than his ability to make a material contribution to its collective life.

The Dominance of Culture

During the upper or late Paleolithic era (ca. 35,000-10,000 B.C.E.), culture, meaning everything about humans that is not inherited biologically, was increasingly determinant in human life. Paleolithic people were not on an endless and allconsuming quest to provide for the necessities of life. They spent less time on such things than we do today. Therefore, they were able to find time to develop speech, religion, and artistic expression. Wall paintings, small clay and stone figurines of female figures (which may reflect concerns about fertility), and finely decorated stone and bone tools indicate not just artistic ability but also abstract and symbolic thought.

The end of the glacial era marked the beginning of the Mesolithic, or Middle Stone Age (ca. 10,000-8000 B.C.E.). This period occurred at different times in different places as the climate grew milder, vast expanses of glaciers melted, and sea levels rose. Mesolithic peoples began the gradual domestication of plants and animals and sometimes formed settled communities. They developed the bow and arrow and pottery, and they made use of small flints (microliths) and

fish-hooks.

Social Organization, Agriculture, and Religion

No one really knows why settlement led to agriculture. As population growth put pressure on the local food supply, gathering activities demandedmoreformalcoordination and organization and led to the development of political leadership. This leadership and the perception of safety in numbers may have prevented the traditional breaking away to form other similar communities in the next valley, as had happened when population growth pressured earlier groups. In any case, people no longer simply looked for favored species of plants and animals where they occurred naturally. Now they introduced these species into other locations and favored them at the expense of plant and animal species that were not deemed useful. Agriculture had begun.

These peoples of the Neolithic era, or New Stone Age (ca. 8000-6500 B.C.E.), organized sizable villages. Jericho, which had been setled before the agricultural revolution, grew into a fortified town complete with ditch, stone walls, and towers and sheltered perhaps 2,000 inhabitants. Catal Huyik in southern Turkey may have been even larger.

The really revolutionary aspect of agriculture was not simply that it ensured settled communities a food supply. The true innovation was that agriculture was portable. For the first time, rather than looking for a place that provided them with the necessities of life, humans could carry with them what they needed to make a site inhabitable. This portability also meant the rapid spread of agriculture throughout the region.

Religion. Agricultural societies brought changes in the form and organization of formal religious cults. Elaborate sanctuary rooms decorated with frescoes, bulls'horns, and sculptures of heads of bulls and bears indicate that structured religious rites were important to the inhabitants of Catal Huyik.At Jericho,human skulls covered with clay, presumably in an attempt to make them look as they had in life, suggest that these early settlers practiced ancestor worship. In these larger communities the bonds of kinship that had united small hunter-gatherer bands were being supplemented by religious organization, which helped to controlandregulatesocialbehavior.Thenature of this religion is a matter of speculation. Images of a female deity, interpreted as a guardian of animals, suggest the religious importance of women and fertility.

Around 1500 B.C.E., a new theme was depicted on the cliff walls at Tassili-n-Ajer: men herding horses and driving horse-drawn chariots. These drawings indicate that the use of horses and chariots, which had developed over 1,500 years before in Mesopotamia, had now reached the people of North Africa. Chariots symbolized a new, dynamic, and expansive phase in Western culture. Constructed of wood and bronze and used for transport and especially for aggressive warfare, they are symbolic of the culture of early river civilizations, the first civilizations in western Eurasia.

MESOPOTAMIA

Need drove the inhabitants of Mesopotamia—a name that means “between the rivers"—to create a civilization; nature itself offered little for human comfort or prosperity. The up-land regions of the north receive most of the rainfall, but the soil is thin and poor. In the south the soil is fertile, but rainfall is almost nonexistent. There the twin rivers provide life-givingwater but alsobring destructive floods that usually arrive at harvest time. Therefore, agriculture is impossible without irrigation. But irrigation systems, if not properly maintained, deposit harsh alkaline chemicals on the soil, gradually reducing its fertility. In addition, Mesopotamia's only natural resource is clay. It has no metals, no workable stone, no valuable minerals of use to ancient people. These very obstacles pressed thepeopleto cooperative,innovative, and organized measures for survival. Survival in the region required planning and the mobilization of labor, which was possible only through centralization.

Until around 3500 B.C.E., the inhabitants of the lower Tigris and Euphrates lived in scattered villages and small towns. Then the population of the region, which was known as Sumer, began to increase rapidly. Small settlements became increasingly common; then towns such as Eridu and Uruk in what is now Iraq began to grow rapidly. These towns developed in part because of the need to concentrate and organize population in order to carry on the extensive irrigation systems necessary to support Mesopotamian agriculture. These towns soon spread their control out to the surrounding cultivated areas, incorporating the smaller towns and villages of the region. They also fortified themselves against the hostile intentions of their neighbors.

The Ramparts of Uruk

Cities did more than simply concentrate population. Within the walls of the city, men and women developed new technologies and new social and political structures. They created cultural traditions such as writing and literature. The pride of the first city dwellers is captured in Epic of Gilgamesh, the earliest known great heroic poem, which was composed sometime before 2000 B.C.E. In the poem, the hero Gilgamesh boasts of the mighty walls he had built to encircle his city, Uruk:

Go up andwalkon theramparts of Uruk Inspect thebase terrace,examine thebrickwork: Is not its brickwork of burnt brick? Did not theSeven Sages lay its foundations?

Gilgamesh was justifiably proud of his city. In his day (ca. 2700 B.C.E.) these walls were marvels of military engineering; even now their ruins remain a tribute to his age. Archaeologistshave uncovered the remains of theramparts of Uruk, which stretched over five miles and were protected by some 900 semi-circular towers. These massive protective walls enclosed about two square miles of houses, palaces, workshops,and temples. Uruk may with reason be called the first true city in the history of Western civilization.

Tools: Technology and Writing

Changes in society brought changes in technology. The need to feed, clothe, protect, and govern growing urban populations led to major technological and conceptual discoveries. Canals and systems of dikes partially harnessed water supplies. Farmers began to work their fields with improved plows and to haul their produce to town, first on sleds and ultimately on carts. These land-transport devices, along with sailing ships, made it possible not only to produce greater agricultural surplus but also to move this surplus to distant markets. Artisans used a refined potter's wheel to produce ceramic vessels of great beauty. Government officials and private individuals began to use cylinder seals, small stone cylinders engraved with a pattern,to mark ownership.Metalworkers fashioned gold and silver into valuable items of adornment and prestige. They also began to cast bronze, an alloy of copper and tin, which came into use for tools and weapons about 3000B.C.E.

Pictograms. Perhaps the greatest invention of early cities was writing. As early as 700o B.C.E., small clay or stone tokens with distinctive shapes or markings were being used to keep track of animals, goods, and fruits in inventories and bartering. By 3500 B.C.E., government and temple administrators were using simplified drawings—today termed pictograms—that were derived from these tokens to assist them in keeping records of their transactions. Scribes used sharp reeds to impress the pictograms on clay tablets. Thousands of these tablets have survived in the ruins of Mesopotamian cities.

Cuneiform. The first tablets were written in Sumerian, a language related to no other known tongue. Each pictogram represented a single sound, which corresponded to a single object or idea. In time, these pictograms developed into a true system of writing called cuneiform (from the Latin cuneus, “wedge") after the wedge shape of the characters. Finally, scribes took a radical step. Rather than simply using pictograms to indicate single objects, they began to use cuneiform characters to represent concepts. For example, the pictogram for “foot” could also mean “to stand?" Ultimately, pictograms came to represent sounds divorced from any particular meaning.

The implications of the development of cuneiform writing were revolutionary. Since symbols were liberated from meaning, they could be used to record any language. Over the next thousand years, scribes used these same symbols to write not only in Sumerianbut also in the other languages of Mesopotamia,such as Akkadian, Babylonian, and Persian.Writing soon allowed those who had mastered it to achieve greater centralization and control of government, to communicate over enormous distances, to preserve and transmit information, and to express religious and cultural beliefs. Writing reinforced memory, consolidating and expanding the achievements of the first civilization and transmitting them to the future. Writing was power, and for much of subsequent history a small minority of merchants and elites and the scribes in their employ wielded this power. In Mesopotamia, this power served to increase the strength of the king, the servant of the gods.

Gods and Mortals in Mesopotamia

Uruk had begun as a village like any other. Its rise to importance resulted from its significance as a religious site. A world of many cities, Mesopotamia was also a world of many gods, and Mesopotamian cities bore the imprint of the cult of their gods.

Mesopotamian Divinities. The gods were like the people who worshipped them. They lived in a replica of human society, and each god had a particular responsibility. Every object and element from the sky to the brick or the plow had its own active god. The gods had the physical appearance and personalities of humans as well as human virtues and vices. Greater gods such as Nanna and Ufu were the protectors of Ur and Sippar. Others, such as Inanna, or Ishtar, the goddess of love, fertility, and wars, and her husband Dumuzi, were worshiped throughout Mesopotamia. Finally, at the top of the pantheon were the gods of the sky, the air, and the rivers.

The Akkadian Empire. The extraordinary developments in this small corner of the Middle East might have remained isolated phenomena were it not for Sargon (ca. 2334-2279 B.C.E.), king of Akkad and the most important figure in Mesopotamian history. During his long reign of 55 years, Sargon built on the conquests and confederacies of the past to unite, transform, and expand Mesopotamian civilization. Born in obscurity, he was worshipped as a god after his death. In his youth he was the cupbearer to the king of Kish, another Sumerian city.Later,Sargon overthrew his master and conquered Uruk, Ur, Lagash, and Umma. This made him lord of Sumer. Such glory had satisfied his predecessors, but not Sargon. Instead, he extended his military operations east across the Tigris, west along the Euphrates, and north into modern Syria, thus creating the first great multiethnic empire stateintheWest.

The Akkadian state—so named by contemporary historians for Sargon's capital at Akkad—consisted of a vast and heterogeneous collection of city-states and territories. Sargon attempted to rule it by transforming the traditions of royal government. Rather than eradicating the traditions of conquered cities,he allowed them to maintain their own institutions but replaced many of their autonomous ruling aristocracies with his own functionaries. At the same time, however, he tried to win the loyalty of the ancient cities of Sumer by naming his daughter high priestess of the moongod Nanna at Ur. He was thus the first in a long tradition of Near Eastern rulers who sought to unite his disparate conquests into a true state.

The Akkadian state proved as ephemeral as Sargon's accomplishments were lasting. All Mesopotamian states tended to undergo a cycle of rising rapidly under a gifted military commander and then beginning to crumble under the internal stresses of dynastic disputes and regional assertions of autonomy. Thus weakened, they could then be conquered by other expanding states. First Ur, under its Sumerian king and first law codifier, Shulgi (2094-2047 B.C.E.), and then Amoritic Babylonia, under its great ruler, Hammurabi (1792-1750 B.C.E.), assumed dominance in the land between the rivers. From about 2000 B.C.E. on, the political and economic centers of Mesopotamia were in Babylonia and in Assyria, the region to the north at the foot of the Zagros Mountains.

Hammurabi and the Old Babylonian Empire

In the tradition of Sargon, Hammurabi expanded his state through arms and diplomacy. He expanded his power south as far as Uruk and north to Assyria. In the tradition of Shulgi, he promulgated an important body of law, known as the Code of Hammurabi. In the words of its prologue, this codesought:

To cause justice to prevail in the country To destroy the wicked and the evil, That the strong may not oppress the weak.

Law and Society. As the favored agent of the gods, the king had responsibility for regulating all aspects of Babylonian life, including dowries and contracts, agricultural prices and wages, and commerce and money lending. Hammurabi's code addresses professional behavior of physicians, veterinarians, architects, and boat builders. It offers a view of many aspects of Babylonian life, though always from the perspective of the royal law. The code lists offenses and prescribes penalties, which vary according tothe social status ofthevictim and the perpetrator. Hammurabi's code thus creates a picture of a prosperous society composed of threelegallydefined social strata: a well-to-do elite, the mass of the population, and slaves. Each group had its own rights and obligations in proportion to its status.Even slaves enjoyed some legal rights and protection,could marry free persons,and might eventually obtainfreedom.

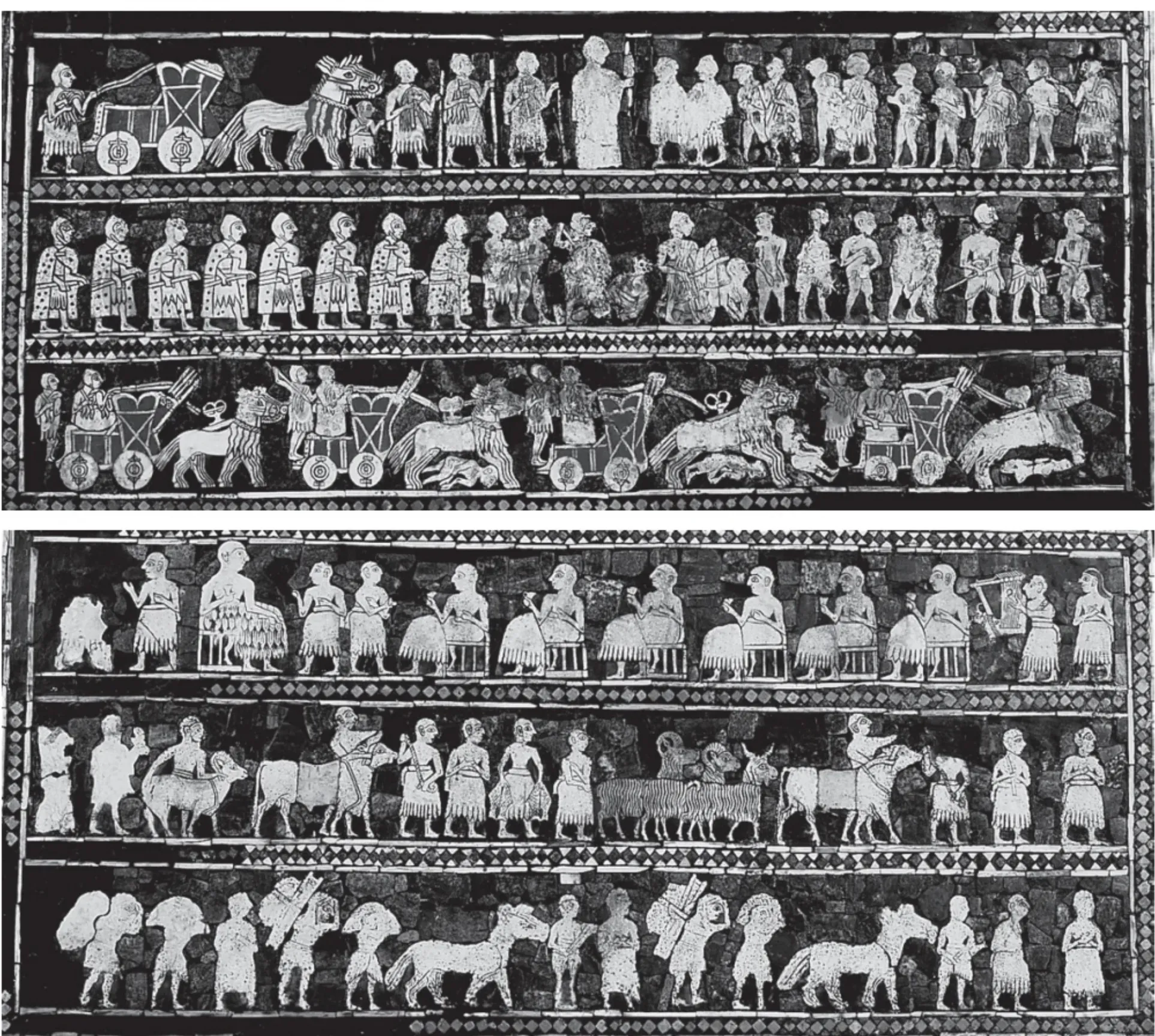

■The Standard of Ur, made of shells, lapis lazuli, and limestone, was found at Ur. In the top panel, known as War, soldiers and horse-drawn chariots return victorious from battle. In the lower panel Peace,the king celebrates the victory, captives are paraded before him, and the conquered people bring him tribute.

The Code of Hammurabi was less a royal attempt to restructure Babylonian society than an effort to reorganize, consolidate, and preserve previous laws in order to maintain the established social and economic order.What innovation it did show was in the extent of such punitive measures as death or mutilation.Penalties in earlier codes had been primarily compensation in silver orvaluables.

Mathematics. Law was not the only area in which the Old Babylonian kingdom began an important tradition. To handle the economics of business and government administration, Babylonians developed the most sophisticated mathematical system known before the fifteenth century C.E. Babylonian mathematics was based on a numerical system from 1 to 60. (Today we still divide hours and minutes into 60 units.)Babylonian mathematicians devised multiplication tables and tables of reciprocals. They also devised tables of squares and square roots,cubes and cube roots, and other calculations needed for computing such important figures as compound interest.Although Babylonian mathematicians were not interested primarily in theoretical problems and were seldom given to abstraction, their technical proficiency indicates the advanced level of sophistication with which Hammurabi's contemporaries could tackle the problems of living in a complex society.

For all its achievements, Hammurabi's state was no more successful than those of his predecessors at defending itself against internal conflicts or external enemies. Despite his efforts, the traditional organization that he inherited from his Sumerian and Akkadian predecessors could not ensure orderly administration of a far-flung collection of cities.Hammurabi's son lost over half of his father's kingdom to internal revolts.Weakened by internal dissension,the kingdom fell to a new and potent force in Western history: theHittites.

The Hittite Empire. The Hittite state emerged in Anatolia in the shadow of Mesopotamian civilization. The Hittite court reflected Mesopotamian influence in its art and religion and in its adaptation and use of cuneiform script. Unlike the Sumerians, the Semitic nomads, the Akkadians, and the Babylonians, the Hittites were an Indo-European people. Their language was part of the linguistic family that includes most modern European languages as well as Persian, Greek, Latin, and Sanskrit. From their capital of Hattushash (modern Bogazkoy in Turkey), they established a centralized state based on agriculture and trade in the metals mined from the ore-rich mountains of Anatolia and exported to Mesopotamia.Perfecting the light horse-drawn war chariot, the Hittites expanded into northern Mesopotamia and along the Syrian coast. They were able to destroy the Babylonian state around 1600 B.C.E. The Hittite Empire was the chief political and cultural force in western Asia from about 1400 to 1200 B.C.E. Its gradual expansion south along the coast was checked at the battle of Kadesh about 1286 B.C.E.,when Hittite forces encountered the army of an even greater and more ancient power:theEgypt ofRamses II.

THE GIFT OF THE NILE

Like that of the Tigris and Euphrates valleys, the rich soil of the Nile Valley can support a dense population. There, however, the similarities end. Unlike the Mesopotamian flood-plain, the Nile floodplain required little effort to make the land productive. Each year, the river flooded at exactly the right time to irrigate crops and to deposit a layer of rich, fertile silt.

The Nile flows from south to north, emptying into the Mediterranean Sea. South of the last cataracts (rapids or falls), the fertile upriver region called Upper Egypt is about eight miles wide and is flanked by high desert plateaus. Downriver, in Lower Egypt near the Mediterranean, the Nile spreads across a lush marshy delta more than one hundred miles wide. Egypt knew only two environments: the fertileNileValley and the vast wastes of theSahara Desert surrounding it. This inhospitable and largely uninhabitable region limited Egypt's contact with outside influences. Thus while trade, communication, and violent conquest characterized Mesopotamian civilization,Egypt knew self-sufficiency, an inward focus in culture and society, and stability. In its art, political structure, society, and religion, the Egyptian universe was static. Nothing was ever expected to change.

The earliest sedentary communities in the Nile Valley appeared on the western margin of the Nile Delta around 4000 B.C.E. In villages such as Merimda, which had a population of over 10,000, huts constructed of poles and adobe bricks huddled together near wadis, fertile riverbeds that were dry except during the rainy season. Farther south, in Upper Egypt, similar communities developed somewhat later but achieved an earlier political unity and a higher level of culture. By around 3200 B.C.E., Upper Egypt was in contact with Mesopotamia and had apparently borrowed something of that region's artistic and architectural traditions. During the same period, Upper Egypt

developed a pictographic script.

These cultural achievements coincided with the political centralization of Upper Egypt under a series of kings. Probably around 3150 B.C.E.,King Narmer or one of his predecessors in Upper Egypt expanded control over the fragmented south, uniting Upper and Lower Egypt and establishing a capital at Memphis on the border between these two regions. For over 2,500 years, the Nile Valley, from the first cataract to the Mediterranean,enjoyed the most stable civilization theWestern world has ever known.

Tending the Cattle of God

Historians divide the vast sweep of Egyptian history into 31 dynasties, regrouped in turn into four periods of political centralization: pre- and early dynastic Egypt (ca. 3150-2770 B.C.E.), the Old Kingdom (ca. 2770-2200 B.C.E.), the Middle Kingdom (ca.2050-1786 B.C.E.), and the New Kingdom (ca. 1560-1087 B.C.E.). The time gaps between kingdoms were periods of disruption and political confusion termed intermediate periods. While minor changes in social, political, and cultural life certainly occurred during these centuries,the changes were less significant than the astonishingstability and continuity of thecivilizationthat developed along the banks of the Nile.

God Kings. Divine kingship was the cornerstone of Egyptian life. Initially, the king was the incarnation of Horus, a sky and falcon god. Later, the king was identified with the sun-god Ra (subsequently known as Amen-Re, the great god), as well as with Osiris, the god of the dead. As divine incarnation, the king was obliged above all to care for his people. Unlike the rulers in Mesopotamia, the kings of the Old Kingdom were not warriors but divine administrators. Protected by the Sahara,Egypt had few external enemies and no standing army. A vast bureaucracy of literate court officials and provincial administrators assisted the godking. They wielded wide authority as religious leaders, judicial officers, and, when necessary, military leaders. A host of subordinate overseers, scribes, metalworkers, stonemasons,artisans,and tax collectors rounded out the royal administration.At thelocal level,governors administered provinces called nomes,the basic units of Egyptian local government.

The Pyramids. During the Old and Middle Kingdoms, great pyramid temple-tomb complexes more imposing than the Great House were built for the kings. Within the temples, priests and servantsperformedritualsto serve thedead kings just as they had served the kings when they were alive. Even death did not disrupt the continuity that was so vital to Egyptian civilization. The cults of dead kings reinforced the monarchy, since veneration of past rulers meant veneration of the reigning king's ancestors.

Building and equipping the pyramids focused and transformed Egypt's material and human resources.Artisans had to be trained, engineering and transportation problems had to be solved, quarrying and stoneworking techniques had to be perfected, and laborers had to be recruited. In the Old Kingdom, more than 70,000 workers at a time were employed in building these great temple-tombs. In comparison, the great Ziggurat of Ur, built around 2000 B.C.E.. The pyramids were constructed by peasants working when the Nile was in flood and they could not till the soil. Although actual construction was seasonal, the work was unending. No sooner was one complex completed than the next was begun.

Democratization of theAfterlife

In the Old Kingdom, future life was available through theking.Thegravesofthousandsofhis attendants and servants surrounded his temple.All the wealth, labor, and expertise of the kingdom thus flowed into these temples, reinforcing the position of the king. Like the tip of a pyramid, the king was the summit, supported by all of society.

BETWEENTWOWORLDS

City-based civilization was an endangered species throughout antiquity. Just beyond the well-tilled fields of Mesopotamia and the fertile delta of the Nile lay the world of the Semitic tribes of semi-nomadic shepherds and traders. Of course, not all Semites were nonurban. Many had formed part of the heterogeneous population of the Sumerian world. Sargon's Semitic Akkadians and Hammurabi's Amorites created great Mesopotamian nation-states, adopting the ancient Sumerian cultural traditions.Along the coast of Canaan, other Semitic groups established towns and joined in the trade between Egypt and the north. But the majority of Semitic peoples continued tolive a life that was radically different from that of the people of the floodplain civilizations. From these, one small group, the Hebrews, emerged to establish a religious and cultural tradition that was unique in antiquity.

The Hebrew Alternative

Sometime after 2000 B.C.E.,small Semitic bands under the leadership of patriarchal chieftains spread into what is today Syria,Lebanon,Israel, and Palestine.These bands crisscrossed the Fertile Crescent, searching for pasture for their flocks. Occasionally, they participated in the trade uniting Mesopotamia and the towns of the Mediterranean coast. For the most part, however, they pitched their tents on the outskirts of towns only briefly, moving on when their sheep and goats had exhausted the supply of pasturage. Semitic Aramaeans and Chaldeans brought with them not only their flocks and families, but Mesopotamian culture as well.

Mesopotamian Origins. Hebrew history records such Mesopotamian traditions as the story of the flood (Genesis 6-10), legal traditions strongly reminiscent of those of Hammurabi, and the worship of the gods on high places. Stories such as that of the Tower of Babel (Genesis 11) and the garden of Eden (Genesis 2-4) likewise have a Mesopotamian flavor, but with a difference. For these wandering shepherds, urban culture was a curse. In the Hebrew Bible (the Christian Old Testament) the first city was built by Cain, the first murderer. The Tower of Babel, probably a ziggurat, was a symbol not of human achievement but of human pride.

At least some of these wandering rejected the gods of Mesopotamia. Religion among these nomadic groups focused on the specific divinity of the clan.In the case of Abraham, this was the god El. Abraham and his successors were not monotheists. They simply believed that they had a personal pact with their own god. In its social organization and cultural traditions,Abraham's clan was no different from its neighbors.These independent clanswere ruled by a senior male (hence the Greek term patriarch—“rule by the father"). Women,whetherwives,concubines,orslaves,weretreated as distinctly inferior, virtually as property.

Egypt and Exodus. Some of Abraham's descendants must have joined the steady migration from Canaan into Egypt that took place during the Middle Kingdom and the Hyksos period. Although they were initially well treated, after the expulsion of the Hyksos in the sixteenth century B.C.E., many of the Semitic settlers in Egypt were reduced to slavery. Around the thirteenth century B.C.E., a small band of Semitic slaves numbering fewer than 1,000 left Egypt for Sinai and Canaan under the leadership of Moses. The memory of this departure, known as the Exodus, became the formative experience of the descendants of those who had taken part and those who later joined them. Moses, a Semite who carried an Egyptian name and who, according to tradition, had been raised in the royal court, was the founder of the Israelite people.

During the years that they spent wandering in the desert and then slowly conquering Canaan, the Israelites forged a new identity and a new faith.From the Midianites of the Sinai Peninsula, they adopted the god Yahweh as their own. Although composed of various Semitic and even Egyptian groups, the Israelites adopted the oral traditions of the clan of Abraham and identified his god, El, with Yahweh. They interpreted their extraordinary escape from Egypt as evidence of a covenant with this god, a treaty similar to those concluded between the Hittite kings and their dependents. Yahweh was to be the Israelites'ex-clusive god; they were to make no alliances with any others. They were to preserve peace among themselves, and they were obligated to serve Yahweh with arms.This covenant was embodied in the law of Moses, a series of terse absolute commands("Thou shall not.")that were quite unlike the conditional laws of Hammurabi ("if...then.."). Inspired by their new identity and their new religion, the Israelites swept into Canaan. Taking advantage of the vacuum of power left by the Hittite-Egyptian standoff following the battle of Kadesh, they destroyed or captured the cities of the region. In some cases, the local population welcomed the Israelites and their religion. In other places, the indigenous people were slaughtered down to the last man, woman, and child.

A King Like All the Nations

During its first centuries, Israel was a loosely organized confederation of tribes whose only focal point was the religious shrine at Shiloh.This shrine, in contrast with the temples of other ancient peoples, housed no idols, only a chest, known as the Ark of the Covenant, which contained the law of Moses and mementos of the Exodus. In times of danger, temporary leaders would lead united tribal armies.The power of these leaders, who were called judges in the Hebrew Bible, rested solely on their personal leadership qualities. This charisma indicated that the spirit of Yahweh was with the leader. Yahweh alone was the ruler of the people.

By the eleventh century B.C.E., this disorganized political tradition placed the Israelites at a disadvantage in fighting their neighbors. The Philistines, who dominated the Canaanite seacoast and had expanded inland, posed the greatest threat. By 1050 B.C.E., the Philistines had defeated the Israelites, captured the Ark of the Covenant, and occupied most of their territory. Many Israelites clamored for “a king like all the nations" to lead them to victory. To consolidate their forces, the Israelite religious leaders reluctantly established a kingdom. Its first king was Saul, and its second was David.

David (ca. 1000-962 B.C.E.) and his son and successor, Solomon (ca. 961-922 B.C.E.), brought the kingdom of Israel to its peak of power, prestige, and territorial expansion. David defeated and expelled the Philistines, subdued Israel's other enemies, and created a united state that included all of Canaan from thedesert to the sea.He established Jerusalem as the political and religious capital.Solomon went stillfurther, building a magnificent temple complex to house the Ark of the Covenant and to serve as Israel's national shrine.David and Solomon restructured Israel from a tribal to a monarchical society.

The cost of this transformation was high. The kingdom under David and especially under Solomon grew more tyrannical as it grew more powerful. Solomon behaved like any other king of his time. He contracted marriage alliances with neighboring princes and allowed his wives to practice their own cults. He demanded extraordinary taxes and services from his people to pay for his lavish building projects. When he was unable to pay his Phoenician creditors for supplies and workers, he deported Israelites to work as slaves inPhoenician mines.

Exile

Not surprisingly, the united kingdom did not survive Solomon's death. The northern region broke off to become the Kingdom of Israel with its capital in Shechem. The south, the Kingdom of Judah, continued the tradition of David from his capital of Jerusalem. These small, weak kingdoms did not long maintain their independence. Beginning in the ninth century B.C.E., a new Mesopotamian power, the Assyrians, began a campaign of conquest and unprecedented brutality throughout the Near East. The Hebrew kingdoms were among their many victims. In 722 B.C.E., the Assyrians destroyed the Kingdom of Israel and deported thousands of its people to upper Mesopotamia. In 586 B.C.E., the Kingdom of Judah was conquered by Assyria’s destroyers, the New Babylonian empire under King Nebuchadnezzar II (604-562 B.C.E.). The temple of Solomon was destroyed, Jerusalem was burned, and Judah's elite were deported to Babylon.

The Babylonian captivity ended some 50 years later when the Persians, who had conquered Babylonia, allowed the people of Judah to return to their homeland.Thosewho returned did so with a new understanding of themselves and their covenant with Yahweh, who was now seen as not just one god among many but as the one universal God. This new understanding was central to the development of Judaism.

The fundamental figures in this transformation were Ezra and Nehemiah (fifth and fourth centuries B.C.E.), who were particularly concerned with keeping Judaism uncontaminated by other religious and cultural influences. They condemned those who had remained in Judaea and who had intermarried with foreigners during the exile. Only the exiles who had remained faithful to Yahweh and who had avoided foreign marriages could be the true interpreters of the Torah, or law. This ideal of separatism and national purity came to characterize the Jewish religion in the post-exilic period.

Among its leaders were the Pharisees, a group of zealous adherents to the Torah,who produced a body of oral law termed the Mishnah,or second law,by which the law of Moses was to be interpreted and safeguarded. In subsequent centuries this oral law, along with its interpretation, developed into the Talmud. Pharisees believed in resurrection and in spirits such as angels and devils.

They also believed that a messiah, or savior, would arise as a new David to reestablish Israel's political independence. Among the priestly elite, the hope for a Davidic messiah was seen as more universal: a priestly messiah would arise and bring about the kingdom of glory. Some Jews actively sought political liberation from the Persians and their successors. Others were more intent on preserving ritual and social purity until the coming of the messiah. Still others, such as the Essenes,withdrewintoisolated communities to await the fulfllment of the prophecies.

NINEVEH AND BABYLON